I previously said the professional opinion of mine most likely to have me like—

is that scholars of US foreign policy are far too kind to interwar isolationists. In that post I talked about William Appleman Williams, who is long dead. What about modern scholars?

Well, let’s take a claim by Matthew Connelly: that Franklin D. Roosevelt deceived the American people in the run-up to the war. I’m not going to tackle all the elements of this claim in this post, just this one part about what Americans generally thought about the war.

I do not know if there was any alternative to deceiving the American people, who largely opposed what they perceived to be a war of choice.

Connelly’s claim here is similar to Robert Kagan’s; both believe the Roosevelt administration forced this “war of choice” on a reluctant American people for a greater good.

How much did the American people actually oppose US entry to the war, though?

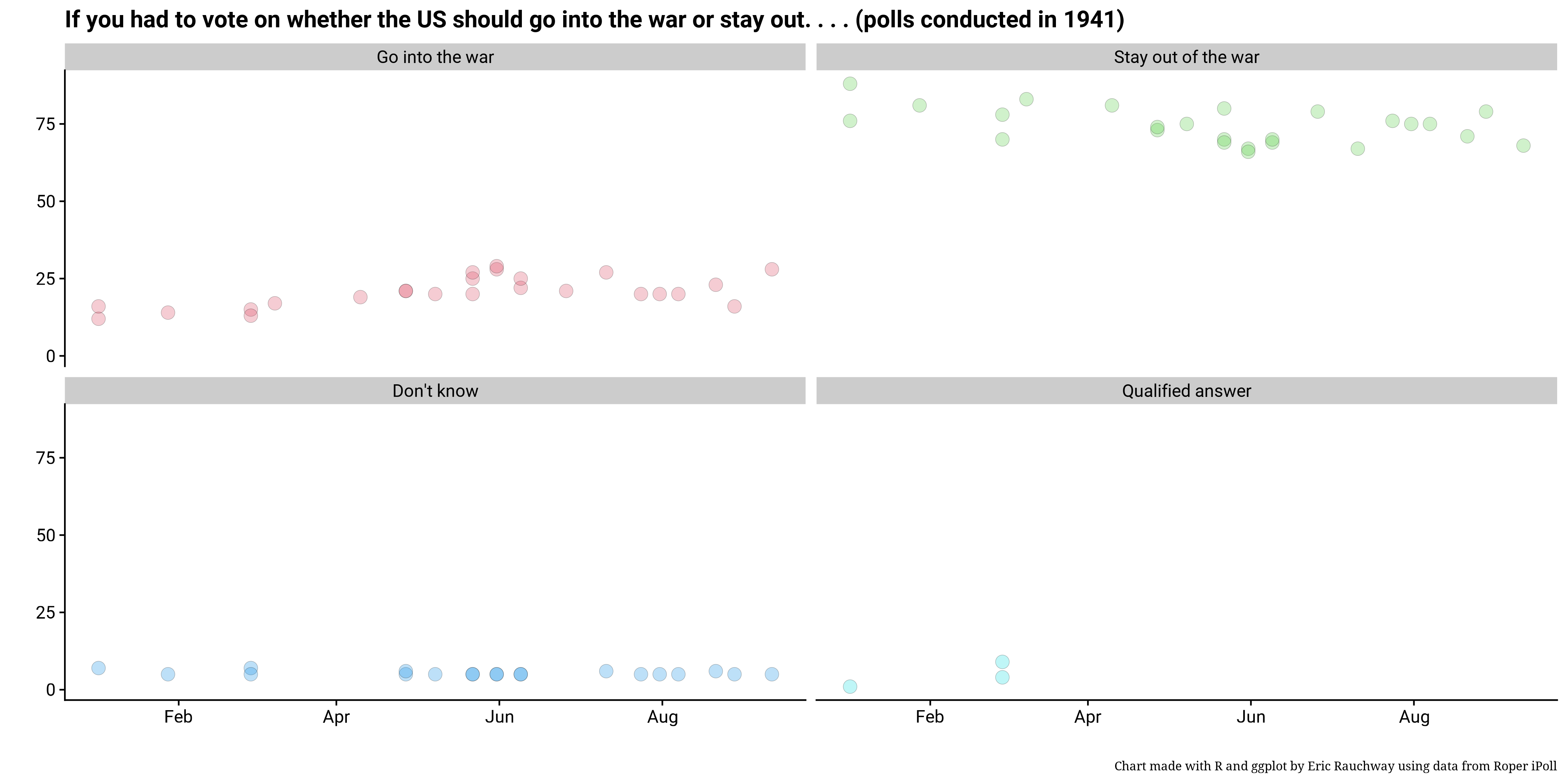

Over the course of 1941, polls frequently asked Americans “If you were asked to vote on the question of the United States entering the war against Germany and Italy [sometimes adding Japan], how would you vote—to go into the war, or to stay out of the war?”

On this question, opinion only very slightly shifts during the year in the direction of “go into the war.” Americans overwhelmingly answer they would vote to “stay out.”

If that was all the information you had, you would say Americans overwhelmingly opposed US entry to the war.

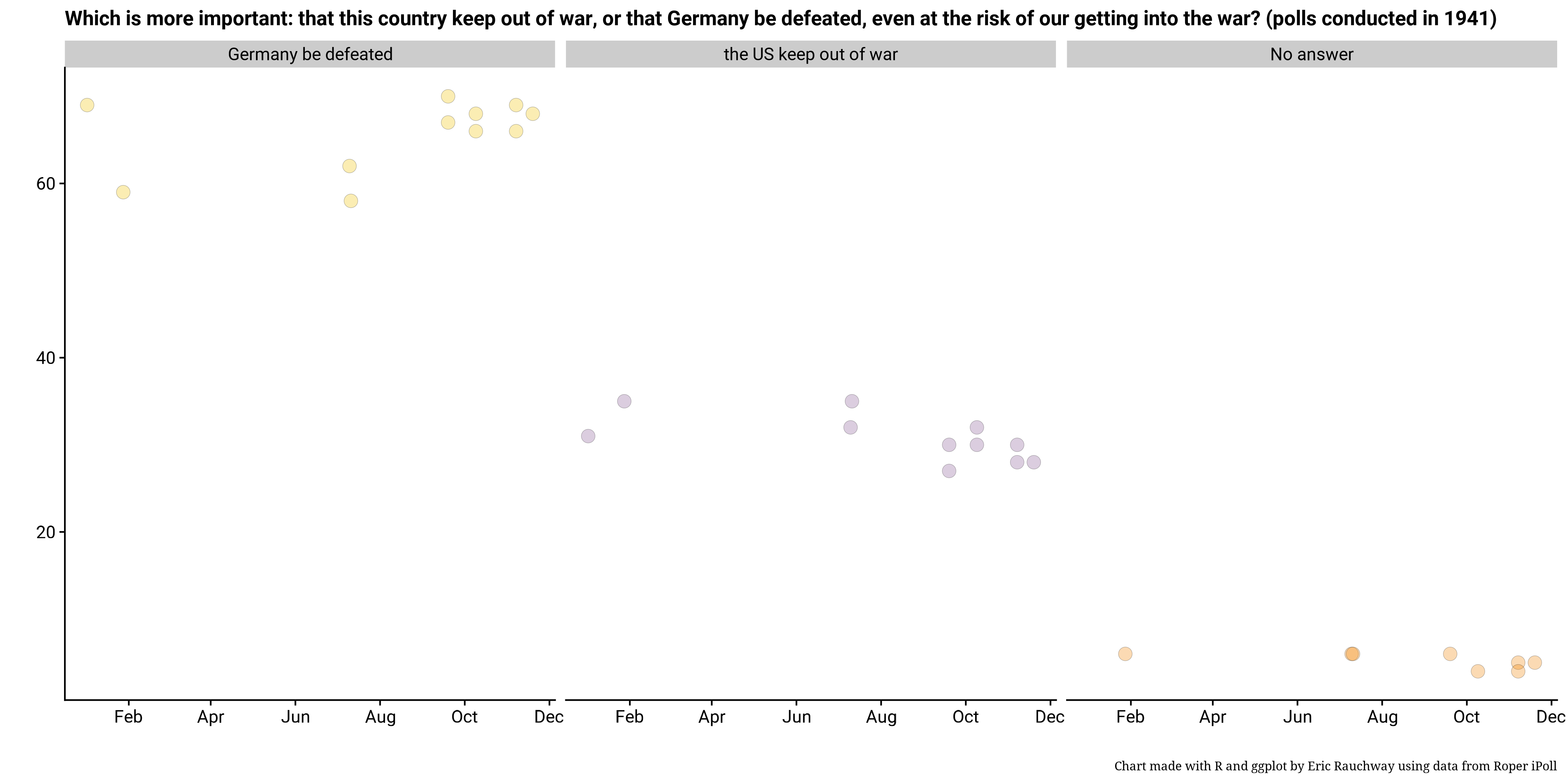

But: over the same period, pollsters also often asked, “Which of these two things do you think is more important—that this country keep out of war, or that Germany be defeated, even at the risk of our getting into the war?”

On this question, Americans quite consistently answered they thought Germany needed to be defeated, even at the risk of US entry to the war. There’s not really that much of a shift.

So considering this second result, it looks like Americans were broadly in favor of the US doing what it could to ensure German defeat, even—explicitly—at the risk of the US getting into the war. In other words, respondents favored what was pretty much the Roosevelt administration’s policy.

You can if you like add one question asked at the start of November 1941: “If our present leaders and military advisors say that the only way to defeat Germany is for this country to go into the war, would you be in favor of this country’s going into the war against Germany?” To that, 70 percent of respondents said “yes,” as against only 24 percent “no” and 6 percent “no opinion.” It appears, then, that respondents were willing to go along with the Roosevelt administration’s judgment about the necessity of US entry to war to defeat Germany.