I published an article in 2019 arguing that “the New Deal was on the ballot in 1932”—that is, that Roosevelt “ran on the New Deal and was elected on it; while 1933 predates modern polling, we may suppose that the voters had a reasonable expectation he would deliver it.”1 My view is contrary to a conventional wisdom which held that Roosevelt did not say much of consequence about the New Deal. I argue that the much tougher burden of proof lies with people who want to prove a negative—that Roosevelt didn’t say anything about key elements of the New Deal—and if you can point to speeches in which he did say things—about support for massively increased public works programs, or stock market regulation, or a lower tariff—then it’s pretty clear where one should come down on the question. But I didn’t have direct evidence about what voters thought, just what Roosevelt said and how vehemently Hoover opposed it.

As it turns out, at about the same time as my article appeared in Modern American History, a scholar named Helmut Norpoth published an article in PS discussing an internal poll conducted by the market research firm J. David Houser for the Hoover campaign close to the 1932 election and arguing that its results show

the Depression was not the dominant issue for American voters in the 1932 election as is commonly assumed. The American people overwhelmingly favored repeal [of Prohibition]. . . . Radical measures such as providing unemployment benefits and a government takeover of the economy enjoyed little support, even among Democrats. . . . Depression, where is thy sting?2

It’s well known among scholars of public opinion polling that market research was closely related to the infant industry, and you can find a discussion of that in standard works.3 So it’s quite reasonable to treat a survey conducted by a market resarch company as a kind of proto-opinion poll.

You would want to be careful, though. Looking at the poll, the author notes,

the Houser Poll inquired whether a respondent (or a family member) was unemployed and [sic; should be “or”] had lost money in a bank failure. It is true that unemployment was more common among FDR Defectors [i.e., people who voted for Hoover in 1928 and intended to vote for Roosevelt in 1932] than among Hoover Loyalists—whether personally or in one’s family—and so was losing money in bank failures (figure 4). Although these experiences may have driven some voters to FDR, the majority of Americans appears not to have been affected personally by the Depression.4

Figure 4, cited there, shows that among the “FDR Defectors,” 13 percent were unemployed, while among “Hoover Loyalists,” 8 percent were unemployed. The thing is, this was at a time when the unemployment rate, as best we can estimate, was around 23 percent.5 So it seems quite likely that the Houser respondents did not represent the overall populace—they were much less likely to be unemployed—and that characterizing their views as representative of “the majority of Americans” is unwarranted; certainly characterizing their experiences as showing who was affected personally by the Depression seems unwarranted. They suffered much less than the average American and we may suppose their attitudes diverged correspondingly from those of the average American.

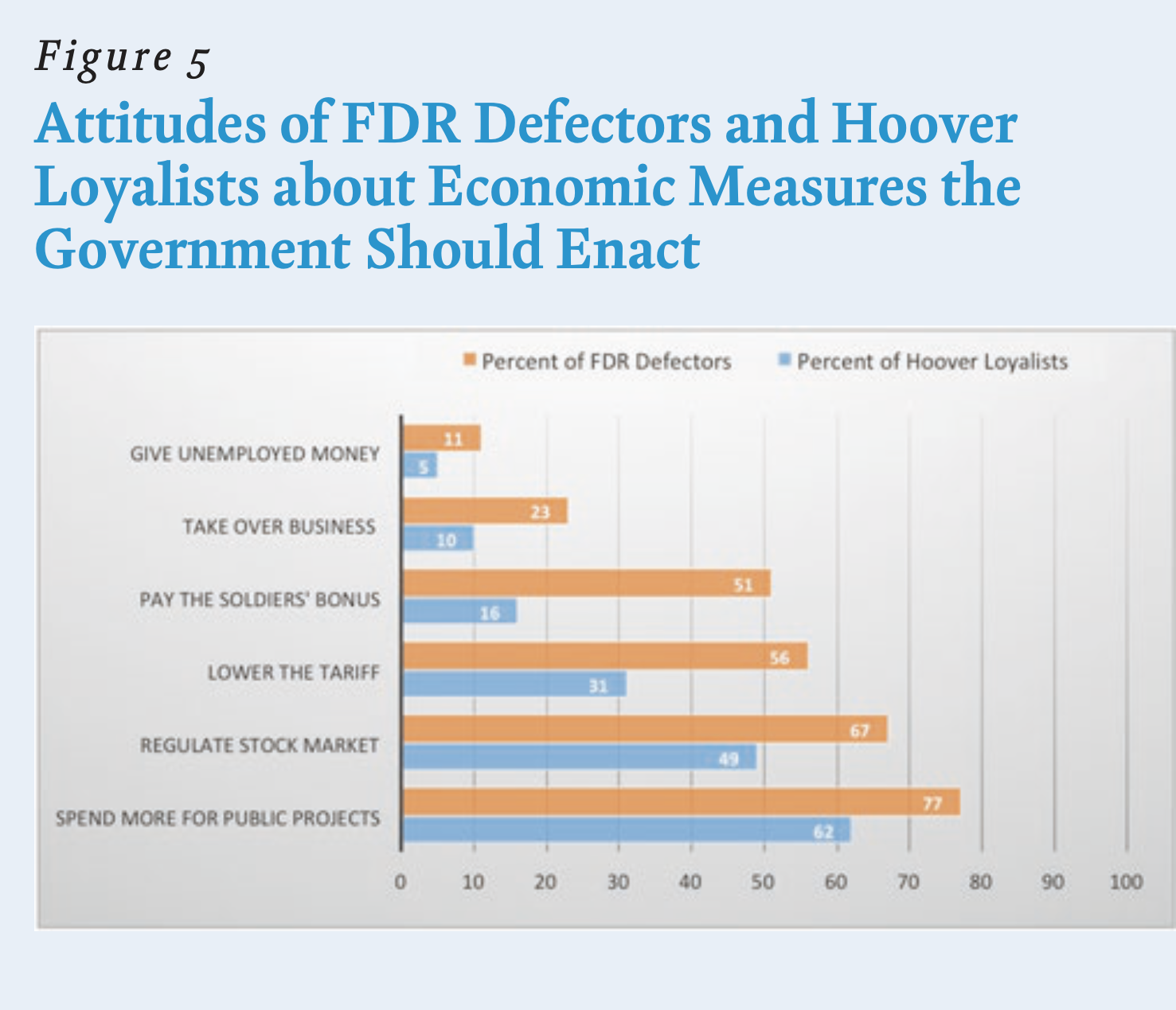

At the same time, it’s useful to note what they did want from the government. I reproduce the article’s next chart, figure 5, here.

Note that, as the author says, hardly anyone—FDR defector or Hoover loyalist—favored giving money to the unemployed or a government takeover of business. Neither Hoover nor Roosevelt favored these, either. Slightly over half of FDR defectors favored paying the veterans’ bonus, as against only sixteen percent of Hoover loyalists; Hoover emphatically opposed the bonus and, infamously, sent the army to burn out the bonus marchers’ encampment and tear gas the protesters, probably causing the death of an infant. Roosevelt didn’t support paying the bonus either (though, as he privately noted, he didn’t think the marchers ought to be gassed) but eventually the Democratic congress would vote for it and pass it over his veto.6

More interesting, though, note what the FDR defectors favored by large margins: a lower tariff (56 percent), stock market regulation (67 percent), and spending more on public works (77 percent). And there’s clear daylight between FDR defectors and Hoover loyalists on these issues—just as there was clear daylight between Roosevelt and Hoover on the stump. Inasmuch as these issues—along with repeal of Prohibition—were key elements of the New Deal featured in Roosevelt’s speeches and campaign literature (as I discussed in the 2019 article), it seems like the New Deal messaging did get through to voters.

Footnotes

Eric Rauchway, “The New Deal Was on the Ballot in 1932,” Modern American History 2, no. 2 (July 2019): 202.↩︎

Helmut Norpoth, “The American Voter in 1932: Evidence from a Confidential Survey,” PS 52, no. 1 (January 2019): 14.↩︎

See Jean M. Converse, Survey Research in the United States: Roots and Emergence, 1890-1960 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).↩︎

Norpoth, “American Voter in 1932,” 17.↩︎

Susan B. Carter et al., eds., Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present, Millennial, 5 vols. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), series Ba475.↩︎

On Hoover, Roosevelt, and the bonus march, see Eric Rauchway and Paul Sparrow, “Why the New Deal Matters” (Roosevelt Reading Festival, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, online, June 15, 2021), 25–33.↩︎