I was looking through a drawer and came across a Bob Dylan-adjacent thing I’d written and forgotten, because my cv has only the academic stuff on it. Given the Discourse around A Complete Unknown, I thought I’d share.

Conor McPherson (who wrote The Weir) wrote and directed Girl From the North Country, a play featuring the songs of Bob Dylan. Set in a boarding-house in Duluth, Minnesota in 1934, it wove Dylan’s songs (performed on Depression-era instruments) through a story about that hard time.

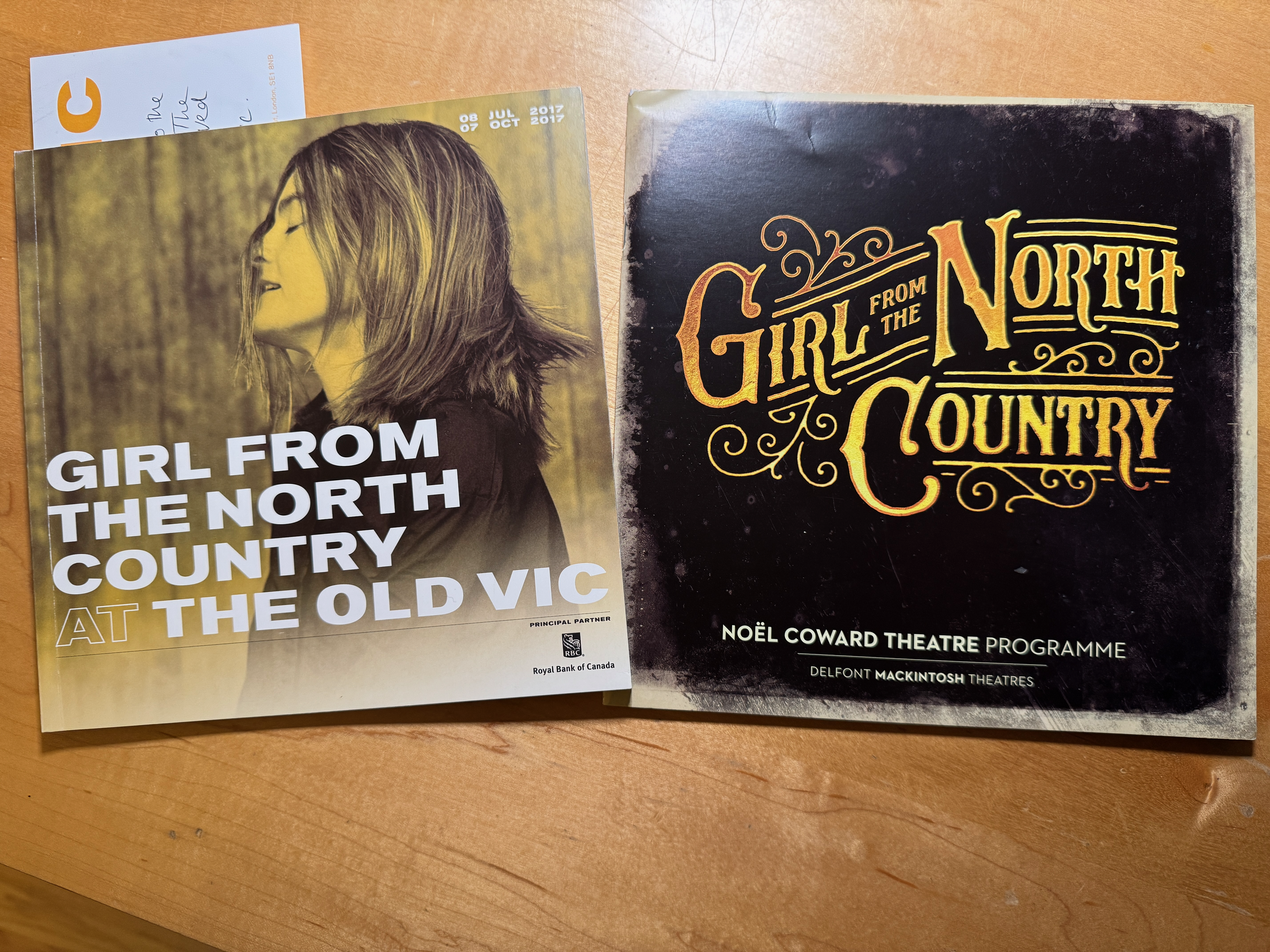

Girl From the North Country was opening at the Old Vic in the summer of 2017; the director of the company producing the program(me) wrote to ask me if I’d contribute an essay on the state of the country, and Minnesota, at that time. So of course I said yes. They sent me the script, I wrote the essay based on the themes I saw in the play, and it went into the programme under the title “A Most Dangerous Time.” When the production moved to the Noël Coward Theatre in the West End a few months later, they kindly kept the essay in the new programme. The text of it appears below the pictures.

The end of 1934 brought a most dangerous time to America. The four Depression winters following the 1929 crash came on hard. Each one worse than the one before, with more out of work, more going hungry, more on the roads, more families broken up and people broken down. Despair stole over the nation’s soul.

But then in 1933 a slender hope seized the citizens who could see that just ever so slightly, things might start getting better. With a new president and a New Deal came new jobs, and a hard, long road along which Americans were nevertheless heading in the right direction, toward work and dignity and an end to the waking nightmare of grinding want. The president, Franklin Roosevelt, knew how terrible a thing this little hope could be. Before, in the forlorn depths of the Depression, Americans had known chiefly how to suffer. But now, with a little hope in them, they sensed their improved prospects, and felt a new restlessness. And it was, Roosevelt worried, ‘disappointed hope, rather than despair, [that] creates revolutions,’ and with this fragile and unrealised hope in them the people stirred that winter on the brink of action, not knowing which way they might lurch.

Minnesotans felt it, the risk that came with a little hope in 1934. They spent the summer enthralled by an industrial civil war that was called out on the state’s radio stations as if it were a football game pitting communists against capitalists.

The fertile prairie state, rich in grain and home to the headwaters of the Mississippi, had become in the industrial age the trucking hub of the American north-west, where the produce of the heartland could be processed, packed and shipped out again. In the years of the Depression, with scarcely any work to be had, the prices people could pay had fallen so low that it was hardly worth a farmer’s while to harvest the crops in the fields, for the pittance they would fetch if brought to market. Wheat went to seed and corn rotted on the stalk.

But in 1934, with business picking up, the flow of goods into the state’s cities resumed, and on this tide of renewed commerce came an opportunity for workers to claim a portion of prosperity. They formed unions, asking for better wages. There were actual communists among the labour leaders, a fact to which the state’s businessmen pointed in rage but, under the circumstances, to little effect. Minnesota boasted a unique achievement: a daily union newspaper, The Organizer, that turned a profit, and it editorialised in a workingman’s voice that ‘these here bosses we got in town keep yellin’ in the papers that communism and payin’ 54½ cents an hour is one an’ the same thing. Well, if that’s what it is I guess I’m a communist an’ I expect most every one in the world . . . must be too.’

The union went on strike, shutting trucking down in Minneapolis for more than a month in the summer heat. Strikers and policemen fought in the streets. In one clash, the policemen ambushed strikers, shooting them in the back as they turned to run, killing a few and sending dozens to the hospital. The governor, Floyd Olson, a member of the Farmer-Labor Party, had to declare martial law and personally prevailed on President Roosevelt to intervene—which he did, assigning a mediator to force a resolution recognising the union, setting minimum wages and maximum hours. The governor and the president believed they had averted revolution by giving a little to the workingmen; the city’s business owners thought the politicians had capitulated to the radicals and they resolved not to let this new state of affairs last.

In November, Olson would have to defend himself against the charge of abetting revolution, explaining that ‘Communists believe in the abolition of private property. We believe in its creation.’ He pulled out a narrow victory, returned to office mainly on account of votes from the workingmen of Minnesota.

It was so easy for Americans then and later to see the clash of classes as a struggle solely between groups of white people. One of the great novelists of the Great Depression, John Steinbeck, made his reputation by writing a novel, In Dubious Battle, based on a California strike—omitting the Mexicans and Mexican Americans who were, in real life, most of the workers.1 It was easier to sell books and inspire white people to sympathy for the poor, if the poor were not also people with darker skins. But race played a major role in shaping the Great Depression.

As one African American observed, black people in America were familiar with hard times long before the 1929 crash. ‘The Negro was born in depression. It didn’t mean too much to him, The Great American Depression, as you call it. There was no such thing. The best he could be is a janitor or shoeshine boy. It only became official when it hit the white man.’

The generation of African Americans who old in the Great Depression had been young in slavery. They could remember when the US government had promised them civil rights and, even better, they could remember when it had failed to deliver, allowing white supremacists to reassert control over first the South, and then much of the rest of the country.

Indeed, by the middle of the 20th century, Minnesota, far in the north of the country and overwhelmingly white, was one of the few US states that did not have laws mandating racial segregation. As racial segregation spread across the South in the early 20th century, black Americans began to move north and west, to better opportunities and less racist cities like Minneapolis and Duluth, where a few hundred African Americans lived by the time of the Depression.

It was moving that gave the greatest hope to African Americans, moving out of the South to a part of the country where white folks’ prejudice, though vicious, did not altogether stop black citizens from staking a claim to their rights.

In the Depression, all kinds of people sought relief by moving. Maybe they had lost a job and a home or a farm and all went on the road together, a family living out of whatever excuse for an automobile they could find, like Steinbeck’s fictitious Joad clan headed from Oklahoma to California in The Grapes of Wrath. Maybe—more often—it was one man alone, leaving his family and relieving them of the burden his empty stomach imposed, hoping he would find work and be able to send a little money home. A woman and her children were more sympathetic, more deserving of charity, without a working-age man in the house.

Often it was the crush of debt that caused families to split up or lose their homes this way; it happened all over the country through the Depression and more in 1934, as a drought set in on the plains. With ever-lower incomes, farmers couldn’t afford their mortgages. Bankers, deprived of their payments, seized homes and farms in a wave of foreclosures.

In 1934, owing to Minnesota, the highest court in the nation was deciding whether the government could do anything to relieve its citizens from this financial crush. Fearing a revolution from the state’s overburdened borrowers, Governor Olson declared that—for a while at least—no sheriff, constable or police officer of the state could carry out a bank’s order to foreclose. The legislature backed him up. As Olson said, he didn’t know if he had the legal authority to stop banks, even temporarily, from taking Minnesotans’ houses, but it was necessary for ‘preserving order within the boundaries of this state.’

Asked to decide whether the state could thus step in to fend off the bankers, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes of the US Supreme Court ruled in 1934 that it might. Even though the right of private property was vital to the American tradition, the Chief Justice cited ‘a growing appreciation of public needs and of the necessity of finding ground for a rational compromise between individual rights and public welfare’ to let Minnesota lawmakers force a sense of mercy on the state’s creditors and permit a moratorium on foreclosures.

Earthly mercy is never so eternal as the divine variety. Even with this relief from state and federal authorities, the Depression would continue to weigh on Americans of all kinds. The state could stave off debt, give you a job, afford relief, but the sum total of the reckoning one owed might still seem insurmountable. The suicide rate generally rises with unemployment, and it peaked in 1932. But even a couple of years onward it had not dropped to an ordinary level. Americans still had an uncertain hope in what this world could offer, and wavered between faith in their ability to save each other, and unbelief.

Eric Rauchway is Professor of History at the University of California, Davis. He’s written five books on US history and a novel.

Footnotes

There were no footnotes in the original, of course, but reading over this sentence I feel compelled to urge you to read Kathryn S. Olmsted, Right Out of California: The 1930s and The Big Business Roots of Modern Conservatism (New York: The New Press, 2015).↩︎