It’s time for Historiographical Hot Take Halloween!1 Let’s spin the wheel and see this year’s Terrifyingly Toasty Take:

There are two (2) historiographical traditions in US policy history that have had genuine serious consequences on US policy—and both of them for ill. To be clear: I distinguish here between history of policy that is consequential on policy, that is, which affected thinking, and that which merely reinforced existing prejudices; there is a lot of the latter.

The first is the Dunning School of Reconstruction, which held that rather than being an essential project of guaranteeing the civil rights of Black Americans, the period was one of unique corruption best left behind. By the 1930s this idea was commonplace among white Americans. When Claude Bowers published The Tragic Era, Franklin Roosevelt wrote him of his experience talking to his friends—“and they have not been confined to Georgians or southerners”—about the book, which “more than any other book in recent years, had a very definite influence on public thought.”2 Even some of Roosevelt’s advisees who actively favored and promoted civil rights, like Harry Hopkins, echoed this view, referring to “the incredibly vicious period of Reconstruction.”3 So although Roosevelt did some things to promote Black civil rights—creating the civil rights section in the Department of Justice—he might have done a good deal more were it not for the pervasive acceptance of the Dunning School among white policymakers.4

The second historiographical school with significant policy influence is the literature denigrating the New Deal itself. Generally this kind of history sets at zero the value of efforts at relief and reform, and asks, how well did the New Deal promote economic recovery?

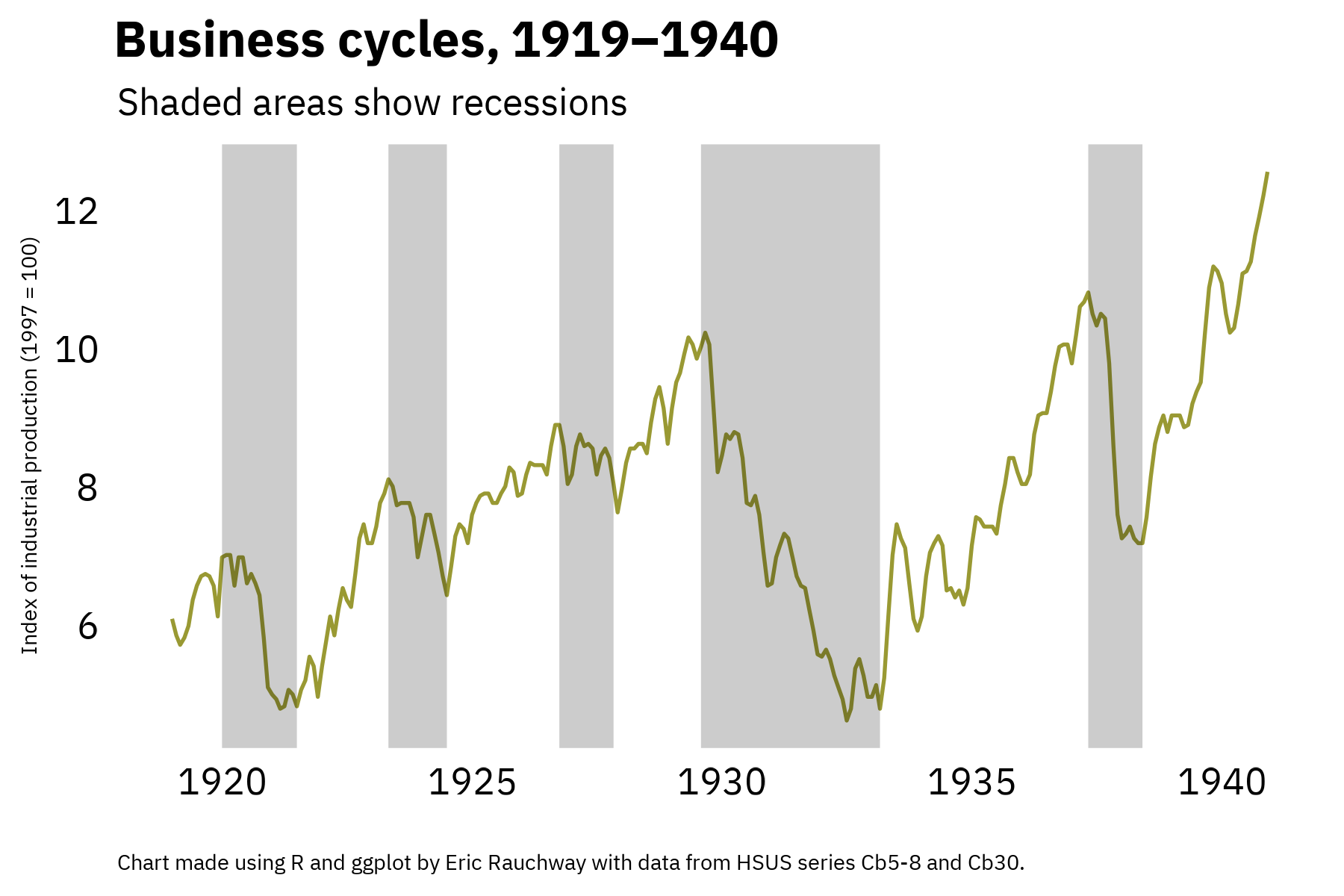

I have written about this view at some length in my Myth America chapter so I will say here only two brief things. First, even if we stipulate that the New Deal slowed recovery, it didn’t slow recovery enough to prevent quite a rapid recovery.

And second, saying effectively, “setting aside relief and reform, how well did the New Deal do at recovery” is in effect saying, “How well did the New Deal restore things to where they were”—an aim Roosevelt expressly and repeatedly rejected. The effect is to produce an entire body of literature which finds—perhaps not surprisingly!—that this popular and effective Democratic policy program didn’t do all that well at promoting a Republican agenda.

And yet, of course, that’s the view of the New Deal that was current among members of the Barack Obama administration, including the president himself; it was frequently referenced by conservatives during the debate over relief and reform during the 2008 financial crisis.

So: two historiographical traditions consequential for US policy—producing bad outcomes. Boo! That’s your Halloween Historiography Hot Take.5

Footnotes

That is too a thing.↩︎

William E. Leuchtenburg, The White House Looks South: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson (Louisiana State University Press, 2005), 35.↩︎

“Harry Hopkins Plan to Help South,” The Progress, August 12, 1938.↩︎

I would argue, though I haven’t room here, that when Roosevelt referred to the New Deal in the Virgin Islands of the United States as an “experiment,” he meant partly that it was an experiment in demonstrating that Black Americans could democratically run a prosperous and orderly society, given the chance—that is, an experiment in disproving the racist foundations of the “tragic era” thesis.↩︎

Bonus corollary, for which there is also no room here! Glib bashing of the John F. Kennedy administration is a subset of both these traditions.↩︎