In addressing various arguments against the New Deal, I’ve generally cited Alexander Field’s fine (and wonderfully titled) A Great Leap Forward.1 I’ve never cited his franker argument from Challenge, which somehow seems relevant today:

The consequences of putting a political party that frequently disparaged government in charge of providing essential government services became clear, however, in the federal government’s response to Hurricane Katrina. While the micropolitics may have seemed like a win for ideologically driven Republicans—provision of shoddy government services could reinforce the claim that only the private sector is able to provide decent services—the philosophy eventually turned a cropper at the polls and has been decisively rejected. It is clear that the American public wants well-thought-out government programs and policies, competently executed.2

So far as the argument about the New Deal goes, Field addresses the “misconceptions and frankly silly claims” he’s seen made “by both economists and non-economists.” Did the New Deal see off the Great Depression altogether? No, but

Although they did not restore us to full employment until the war, New Deal fiscal policies nevertheless operated in the right direction through Roosevelt’s first term.3

He goes on to note that the often cited argument by Ohanian is “unpersuasive,” inasmuch as—for all its shortcomings—the NRA did do its part in “arresting deflation” and anyway in no way constitutes the whole of the New Deal.4

Field concludes—this is 2009—that Barack Obama’s key advisors, notably Lawrence Summers and Tim Geithner, “have been too deferential toward Wall Street.” And he likens “New Deal denialism, as some have called it,” to creationism; that is, that it has no more proper relation to economics as a science than creationism does to biology.5

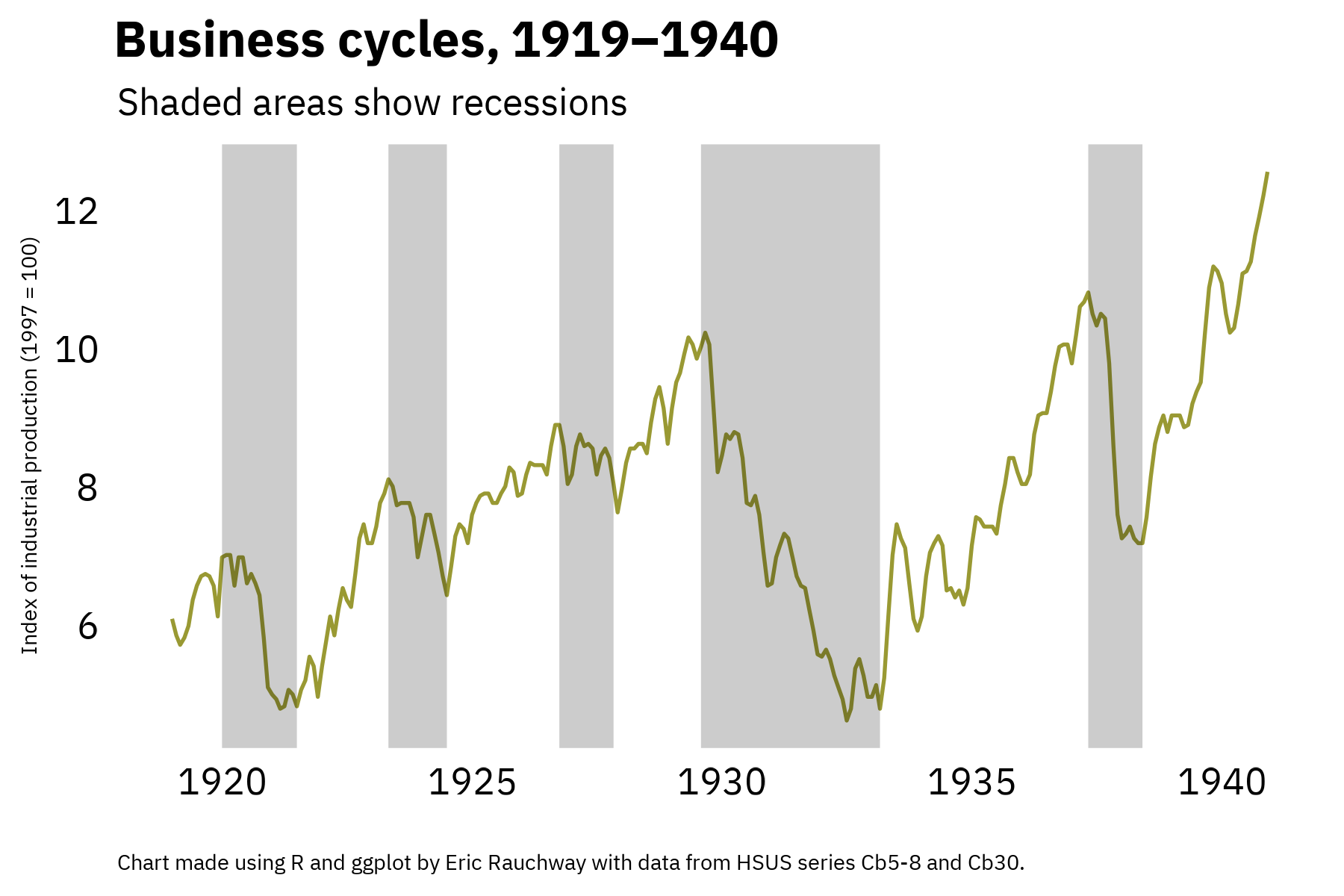

Anyway, it seems like a good enough reason to put up the latest version of a graph I commonly use, depicting U.S. business cycles over the course of the interwar period, using the monthly series of the index of industrial production. The collapse of 1929–1933 is obvious, as is the sharp turn-around in March 1933, and the improvement over the course of the New Deal, with the exception of the 1937–1938 recession.

Footnotes

Alexander Field, A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).↩︎

Alexander Field, “The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Current Crisis,” Challenge 52, no. 4 (July 2009): 95.↩︎

Field, “Great Depression,” 99.↩︎

Field, “Great Depression,” 99.↩︎

Field, “Great Depression,” 104.↩︎