The effort to quantify the dead of the Holocaust inspires a queasy feeling, as of dealing with the genuinely obscene, but it is a necessary methodological substitute for the evidentiary absence at the center of the event: that is to say, we have no representative subjective account of it. That is to say, we have survivors’ accounts but, as Primo Levi (among others) points out, survivors’ accounts are not representative. The representative Jewish experience of the Holocaust was death.

I must repeat: we, the survivors, are not the true witnesses. . . . We survivors are not only an exiguous but also an anomalous minority: we are those who by their prevarications or abilities or good luck did not touch bottom. Those who did so, those who saw the Gorgon, have not returned to tell about it or have returned mute, but they are the ‘Muslims,’ the submerged, the complete witnesses, the ones whose deposition would have a general significance. They are the rule, we are the exception.1

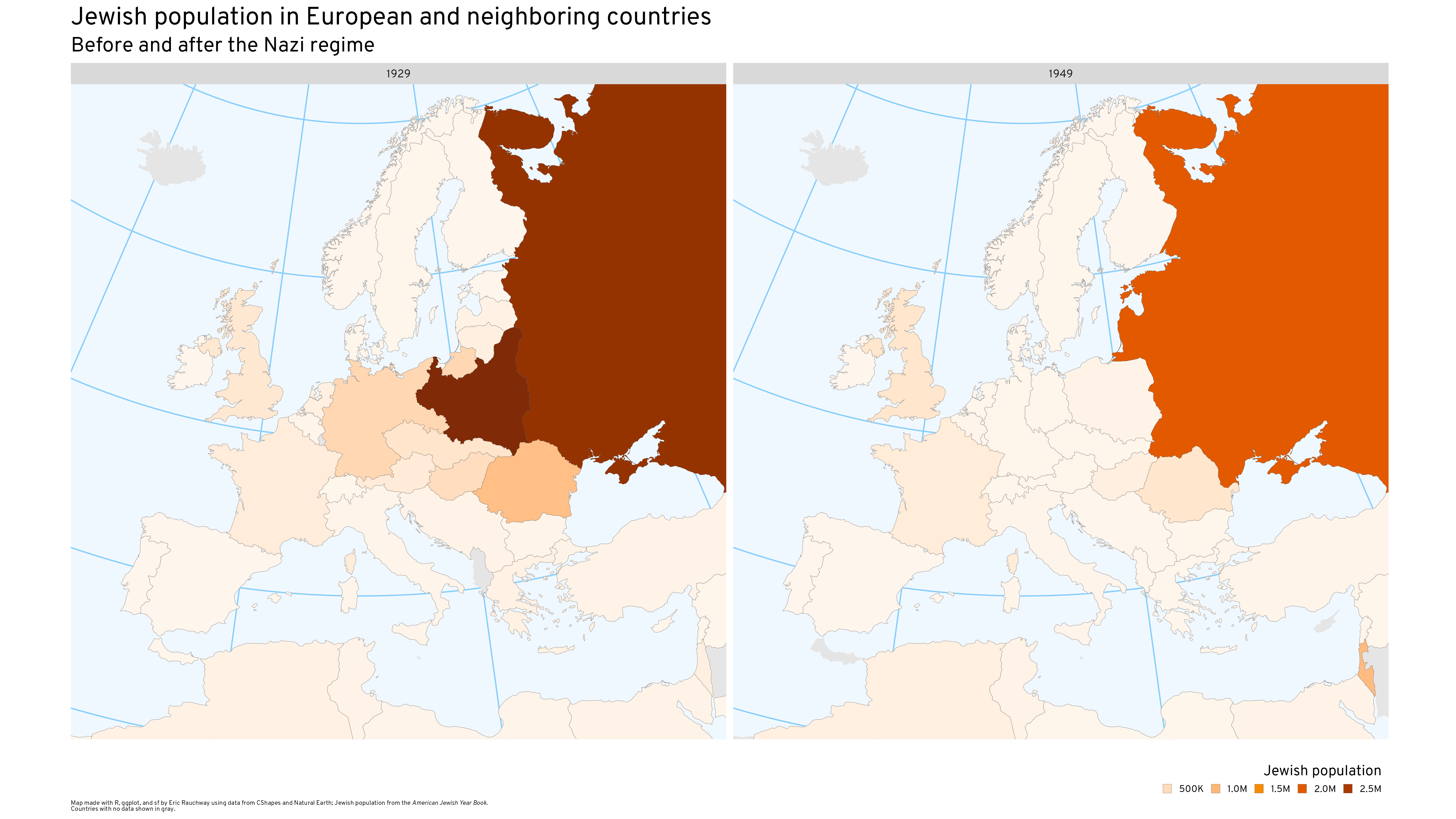

It is a shocking thing to consider: that, for example, of the 3.3 million Jews who lived in Poland in 1939, perhaps 380,000 survived the war. Historians generally use first-hand testimony of great historical events as an indication of what it must have been like to experience the event. A survivor’s testimony cannot serve that purpose when the dead outnumber the survivors by something like 7.6 to 1.

Footnotes

Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved, trans. Raymond Rosenthal (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986), 70.↩︎