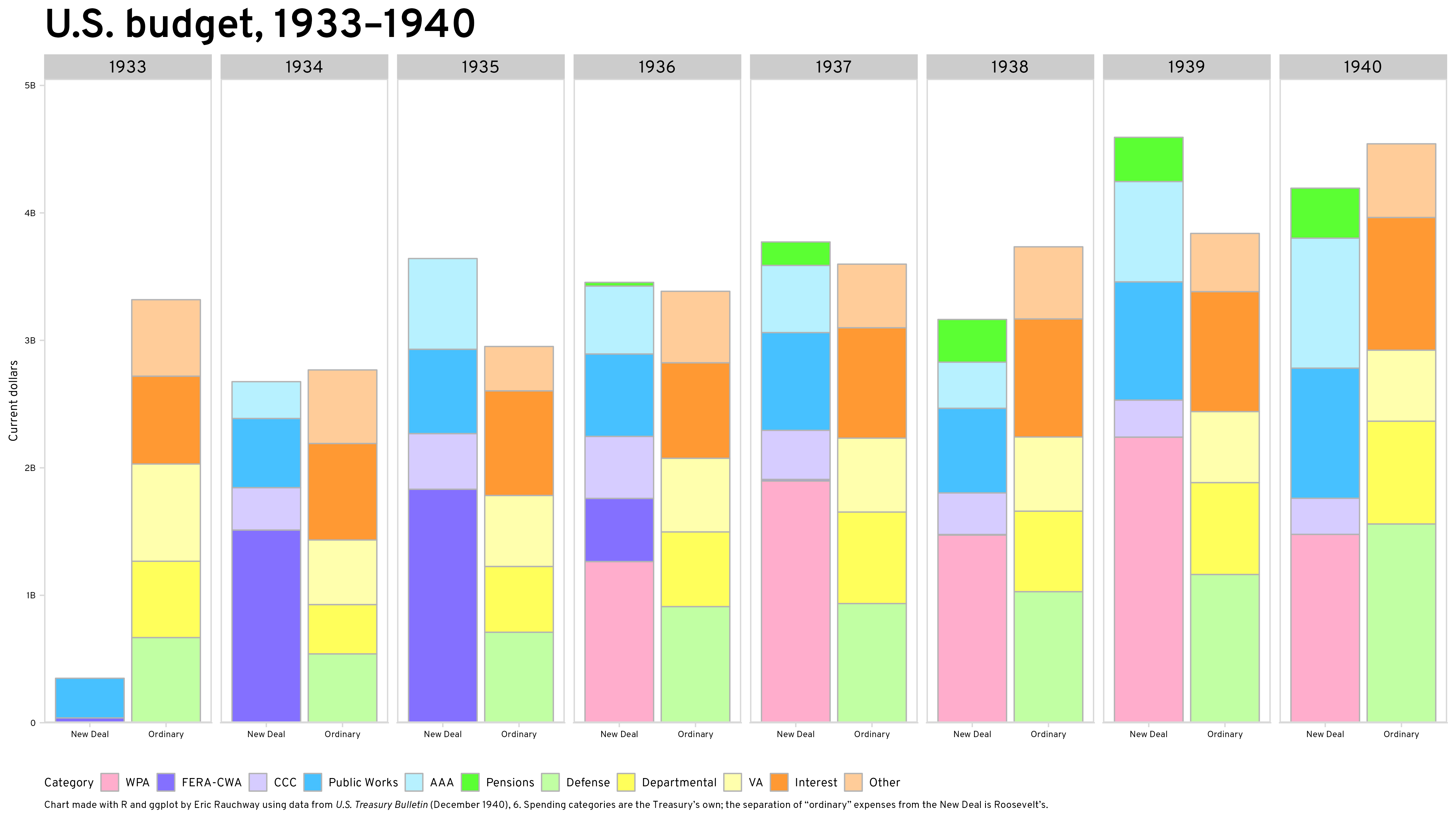

Much as I crankily complain about e-texts (tldr; for scholarly use and for instruction they are not as accessible as they should be), we live in an age of wonderful online documents, including the US Treasury Bulletin, of which one may find the December 1940 number here. And in that number one may find the Treasury’s own breakdown of the New Deal budgets, which I depict here in graphical format.

During the 1932 campaign, Franklin Roosevelt tried (as candidates often do) to have his cake and eat it too—that is, to promise both that he would be more frugal than Herbert Hoover and that he would spend extraordinary sums on unemployment relief as part of his New Deal. Roosevelt gave a respectable cast to this pledge to have it both ways by distinguishing between the “ordinary” expenditures of the federal government, which he would cut, and the necessary emergency expenditures of the New Deal, which would grow as large as they must to provide relief. As he said in his speech on the budget in Pittsburgh, (transcript here) under Hoover “our Federal Government has experienced unprecedented deficits,” which needed paying for in taxation, “a brake on any return to normal business activity.” He proposed therefore to cut the expenditures of the federal government—while excepting the emergency expenditures necessary for the New Deal:

what I am talking about more especially tonight are the taxes which go to the ordinary costs of conducting government year in and year out—and that is where the question of extravagance comes in. There can be no extravagance when starvation is in question; but extravagance does apply to the mounting budget of the Federal Government in Washington during these past four years.

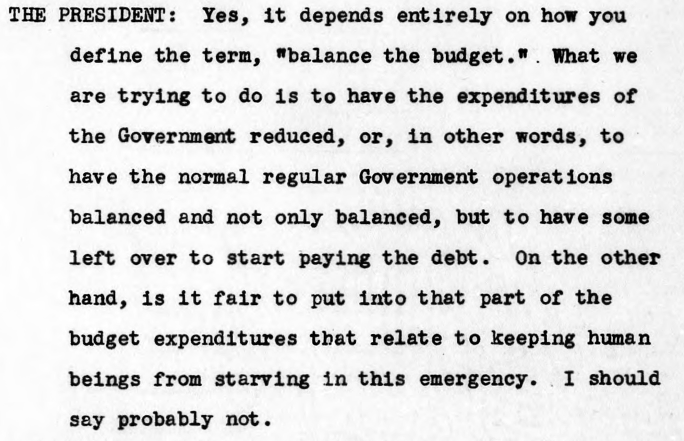

Roosevelt kept budget-cutting a priority, while also preserving this exception, once inaugurated. The first major New Deal measure after the banking and currency legislation was the Economy Act, which gave the president extraordinary powers to cut the budget. On March 24, 1933, just after the passage of the Economy Act, a reporter asked Roosevelt if he would balance the budget, and the president gave an answer that hewed to the distinction, however inventive, he had made during the campaign.

As you can see from the chart, Roosevelt (through his budget-cutting deputy Lewis Douglas) used the Economy Act’s authority to reduce what he considered “ordinary” federal spending in his first budget, and the “ordinary” expenses of the government remained down through his first term. Of course, he more than made up for that drop with New Deal spending.