This is a follow-up to the previous post on Roosevelt’s assessment of the German threat in December 1940, pursuing the big question, “How much of a threat did Germany pose to the United States before Pearl Harbor?” This post looks at the question of Atlantic geography and German ambitions.

Likewise, the military scenarios Roosevelt sketched had little basis in reality. . . . He also stressed the narrowness of the Atlantic, even if not at the obviously most relevant place: “At one point between Africa and Brazil the distance is less than from Washington to Denver, Colorado—five hours for the latest type of bomber.”1

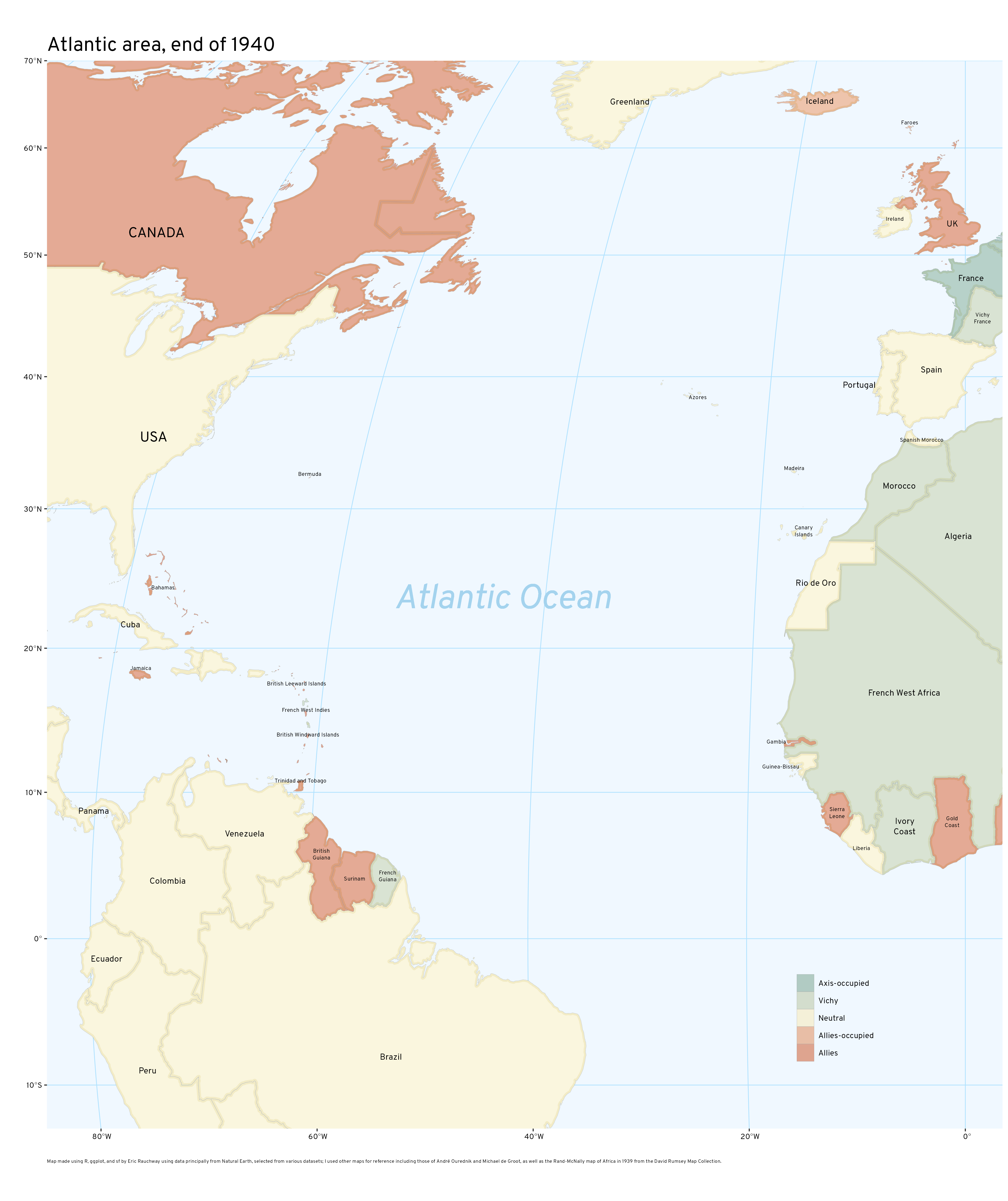

Let’s consider the Atlantic situation at the time of Roosevelt’s speech at the end of 1940.

You can see the short distance from Brazil to West Africa; you can also see that French West Africa was at the time under the jurisdiction of the Vichy regime. France had fallen to Germany in June; Italy had entered the war and struck across North Africa. Though the Italians had failed to take Egypt and were then suffering under British counter-attack, the Germans would shortly organize the Afrika Corps under Erwin Rommel and deploy it to the region.2

The status of West Africa was thus anything but evidently secure at the end of 1940, and indeed would only seem less secure quite soon.

Even as Roosevelt was warning that the Americas were vulnerable to German assault across the Atlantic, Hitler was planning for such an attack. In response to the Roosevelt administration’s September 1940 agreement to trade US destroyers for British bases in the western hemisphere, Hitler told Admiral Raeder that “England-USA must be thrown out of North-West Africa.” He opened negotiations with Spain to trade French Morocco for one of the Canary Islands, to establish a military outpost in the far West of the European hemisphere; he also began to consider whether the Azores could be used “to carry out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States.” German bomber technology would not then support it but nobody could then know of the limits on even the longest-range German bombers then under development, the Heinkel 177.3

In the period between the fall of France and Pearl Harbor, Germany appeared to be at peak power, to Germans and to outside observers alike. Through 1941, aware of the impending Japanese attack, Hitler would continue to plan for a German war on the United States, in which an assault across the Atlantic would play a part.4 There is thus no obvious reason to believe that Roosevelt was wrong, or alarmist, to consider the relative narrowness of the ocean or the possibility of a German aerial assault across its expanse.

Footnotes

John A. Thompson, “The Exaggeration of American Vulnerability: The Anatomy of a Tradition,” Diplomatic History 16, no. 1 (January 1992): 30.↩︎

Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 215.↩︎

Holger H Herwig, “Prelude to Weltblitzkrieg: Germany’s Naval Policy Toward the United States of America, 1939-41,” Journal of Modern History 43, no. 4 (December 1971): 657–58.↩︎

Herwig, “Prelude to Weltblitzkrieg,” 660–62.↩︎