The AHA hosted a Congressional briefing this morning in the Rayburn office building with about 70 people in attendance and a panel including Douglas Irwin, Sharon Ann Murphy, and me. C-SPAN filmed it for later broadcast. My remarks as prepared appear below, though if you should someday watch the C-SPAN recording you’ll know I went off script, based on what Doug had already said.

Good morning. I’m going to speak for a few minutes on the origins of presidential authority to make tariff deals with other countries in the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934.

Franklin Roosevelt first ran for president in 1932 arguing for lower tariffs as part of the New Deal by saying the “outrageously excessive [tariff] rates . . . must come down. . . . by consenting to reduce . . . some of our duties in order to secure a lowering of foreign tariff walls.”1 The idea was to reduce tariffs in exchange for other countries’ doing likewise, so as to open overseas markets for US goods. This is the trade principle known as reciprocity. Opinion polls demonstrate that Roosevelt supporters expected him to reduce tariffs.2 Herbert Hoover vigorously opposed reducing tariffs and warned that if it happened, “The grass will grow in [the] streets of a hundred cities, a thousand towns.”3 Roosevelt won the election; his inaugural parade included a group of men with lawnmowers marching through the streets of Washington, DC.4 Once in office, he acquired the power to negotiate lower tariffs on a reciprocal basis.

To fulfill Roosevelt’s campaign promise, the Reciprocal Tariff Agreement Act of 1934 amended the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 to allow the president to make trade agreements with foreign countries “so that foreign markets will be made available.” The law aimed at “increasing the purchasing power of the American public” and “restoring the American standard of living.”5 It enacted the idea of reciprocity; the US and another country would each agree to lower rates to improve trade between the two. It incorporated an idea of gradualism—in no case could the reduction in rate be more than fifty percent of the Smoot-Hawley rate.6 And although it described bilateral agreements, when those agreements included most-favored-nation clauses—which was language ensuring that any nation signing an agreement would gain any advantage later secured by any other nation signing an agreement—the Roosevelt administration acquired the means to gradually liberalize trade with many parties.7 Within three years the administration negotiated sixteen agreements and more would soon follow, increasing trade among participating countries.8

I want to focus now on the mechanism for reducing tariffs, and for reducing them gradually, which was as important as the general aim of lower tariffs.

Let me talk first about gradualism. Roosevelt appreciated the need for a gentle shift away from protectionism. As he said privately, protectionism might be “all right today” but he opposed it “as a long-term policy,” saying, “in the long run it would work against us and our world trade and our industry.”9 He had similar views about monetary policy; he wanted to devalue the dollar gradually.10 In both cases he knew he wanted to make an ultimately dramatic change in the cost of doing business but he wanted to make it without too much disruption to business plans then in effect. So gradualism was the order of the day.

Second, as to the mechanism: the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act delegated tariff power to the president, who would strike deals with other countries. The point of delegating this power to the president was to lower tariffs. By 1934 it was clear Congress had great difficulty doing so.11

When Congress made tariffs, as both William McKinley and Herbert Hoover found to their disappointment, lawmaking quickly became an exercise in log-rolling—you vote for a tariff increase protecting industry in my district; I’ll vote for a tariff increase protecting industry in your district. Log-rolling tended generally to produce higher rates, as every lawmaker looked to get protection for his district. The tariff became a mechanism for providing constituent service and patronage—a domestic, rather than an international, policy, even though it worked by affecting international trade.

By the time of Smoot-Hawley, protectionist lawmakers described log-rolling not as an unfortunate side effect but as an essential feature of tariff-making. As Reed Smoot said, “the tariff is a domestic matter, and an American tariff must be framed and put into force by the American Congress and administration. No foreign country has a right to interfere.”12

The reciprocal mechanism begun in 1934 let the president reach agreements with foreign countries—much against what Smoot said—and let him do so in broad consultation with various experts throughout the executive branch.

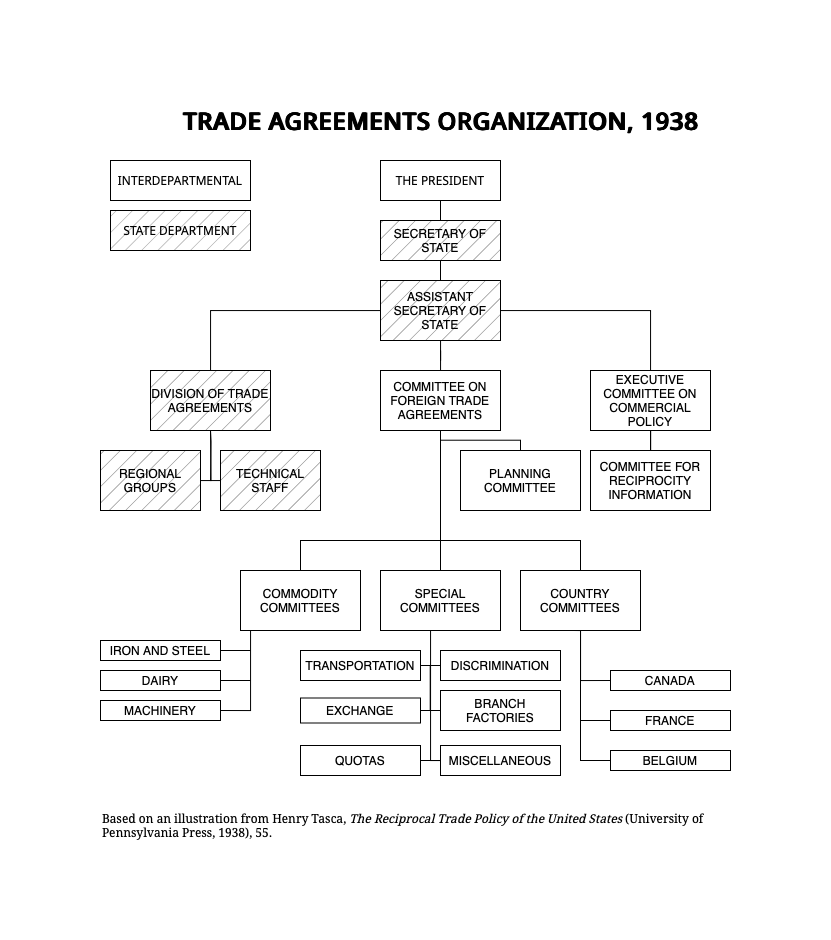

The handout has an organization chart of the trade agreements mechanism set up under the Roosevelt administration.13 As you can see, there are some state department committees, and many more interdepartmental committees—including representatives from commerce, agriculture, treasury, and so on.

This broad range of committees served not only to get input from a variety of sources—thus ensuring everyone got heard—but also to diffuse, and actually to obscure, the process by which a decision got made. A politician or business representative might look at this chart and say to himself, well, this is a nightmare; I don’t know who to lobby—and that’s exactly the point. There were lots of people you could talk to but shy of the president himself, you didn’t know who’s making decisions. And even if you did have access to the president, having this elaborate mechanism allowed the president to say, well, you know, I have multiple, carefully composed expert recommendations; I can’t very well go against them.14 So these economic experts could toil away, untroubled by influence, and recommend action to the president. John Maynard Keynes famously hoped that economics would one day become as dull as dentistry; he meant this as a compliment to his future profession—that it would become boringly professional, rather than heated and political.15 The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (like, as it happens, much of the New Deal) embodied this view.

This emphasis on gradual movement, international agreement, and a mechanism centered in the executive but informed by an array of expert advisors had the intended effect of reaching generally lower tariffs and increasing world trade. By the end of the Roosevelt administration in 1945, twenty-eight agreements were in place and the fifty percent limit in rate reductions had been nearly reached. Congress then extended the authority and allowed another fifty percent reduction.16

Having the president make international agreements shielded legislators from having to vote for a tariff reduction. And it allowed them to reap the benefits of increased exports from their district. It allowed lower rates and increased global trade. Moreover, the real and widespread benefits to the US economy of increased exports helped forge a bipartisan consensus on free trade.17

Footnotes

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Sioux City, IA - Campaign Address,” September 29, 1932, 17, Master Speech File, FDRL.↩︎

Helmut Norpoth, “The American Voter in 1932: Evidence from a Confidential Survey,” PS 52, no. 1 (2019): 17.↩︎

Herbert Hoover, “Address at Madison Square Garden,” in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, Herbert Hoover, 1932–1933 (Government Printing Office, 1977), 669.↩︎

Eric Rauchway, Winter War: Hoover, Roosevelt, and the First Clash Over the New Deal (Basic Books, 2018), 233.↩︎

An Act to Amend the Tariff Act of 1930, Pub. L. 316, 48 US Statutes at Large 943 (1934).↩︎

This was the first measure allowing for presidential negotiation with another country to mutual benefit; the Smoot-Hawley Tariff had previously allowed for what Henry Tasca called “the penalty type of tariff bargaining,” allowing the president to impose punitive tariffs on a country discriminating against the United States. The Reciprocal Trade Policy of the United States: A Study in Trade Philosophy (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1938), 41.↩︎

William R. Allen, “The International Trade Philosophy of Cordell Hull, 1907–1933,” American Economic Review 43, no. 1 (1953): 114.↩︎

Tasca, Reciprocal Trade Policy, 266, 271.↩︎

Roosevelt was speaking here to Hearst emissary Ed Coblentz in January 1933. Rauchway, Winter War, 176.↩︎

Eric Rauchway, The Money Makers: How Roosevelt and Keynes Ended the Depression, Defeated Fascism, and Secured a Prosperous Peace (Basic Books, 2015), 82.↩︎

Tasca finds only three of 21 previous efforts to negotiate reciprocal treaties, which required Senate approval, succeeded. Reciprocal Trade Policy, 43.↩︎

David A. Lake, Power, Protection, and Free Trade: International Sources of U.S. Commercial Strategy, 1887–1939 (Cornell University Press, 1988), 192.↩︎

The diagram is derived from one in Tasca, Reciprocal Trade Policy, 55.↩︎

For an indication that this effect was intended, see the discussion in Reciprocal Trade Policy, 50–66, including the observation that the membership of many committees was not publicized.↩︎

John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Persuasion (Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1933), 373.↩︎

Judith Goldstein, Ideas, Interests, and American Trade Policy (Cornell University Press, 1993), 162–64.↩︎

Michael A. Bailey et al., “The Institutional Roots of American Trade Policy: Politics, Coalitions, and International Trade,” World Politics 49, no. 3 (1997): 309–38; Stephan Haggard, “The Institutional Foundations of Hegemony: Explaining the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934,” International Organization 42, no. 1 (1988): 91–119; Theodore J. Lowi, “American Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political Theory,” World Politics 16, no. 4 (1964): 677–93.↩︎