On January 24, 1943, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill held a joint press conference in Morocco, after some days discussing combined Allied strategy in the Casablanca meeting. (Stalin declined to attend.) They met there—they could meet there—because the US army had begun to assist the British army in clearing the Nazis from North Africa.

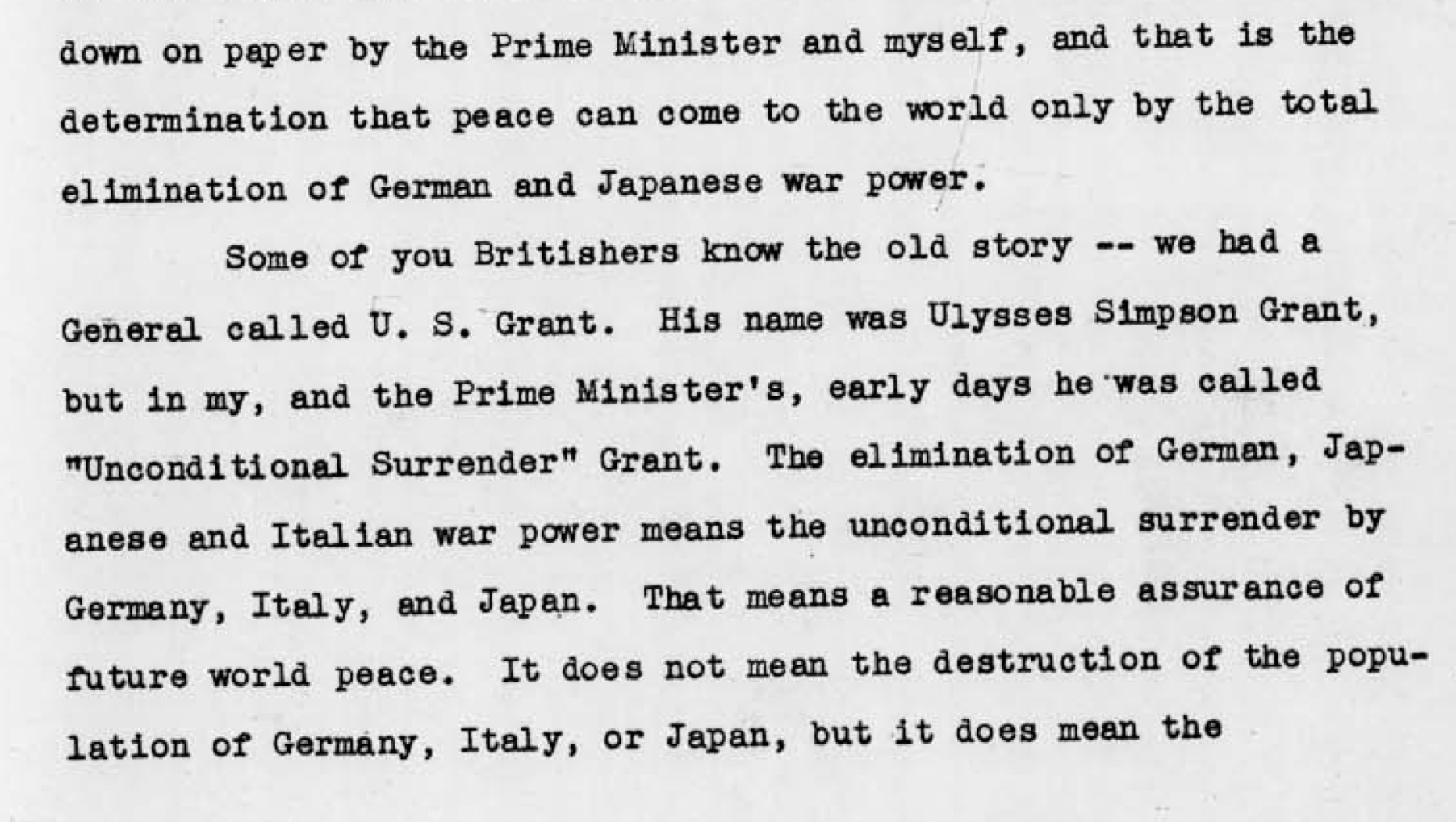

The most important immediate result of the conference was probably the plan for the Combined Bomber Offensive, but the more important in terms of strategy—and one that was very much, like the “United Nations,” like the prioritization of North Africa, Roosevelt’s personal preference—was the announcement of an Allied policy to demand unconditional surrender.

Roosevelt believed peace could only come with the utter defeat of the fascist powers. Not the destruction of their people, as he was quick to stipulate: but the destruction of their ability to make war. For him, the war was, necessarily, a war against fascism, not merely against a particular enemy, and fascism needed to be not only defeated but widely seen to have been defeated.

The demand for unconditional surrender was, and remains, debated in its wisdom. As Marc Gallicchio’s Unconditional establishes quite clearly, though, it was the New Dealers’ position; people on the political right—the pre-war isolationists, chiefly—were the ones who preferred an accommodation with the fascist powers.1

Footnotes

Marc Gallicchio, Unconditional: The Japanese Surrender in World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).↩︎