Barrie A. Wigmore has an article of 1987 asking whether the gold panic of early 1933 was caused by fears of devaluation, to which he answers “yes.”1

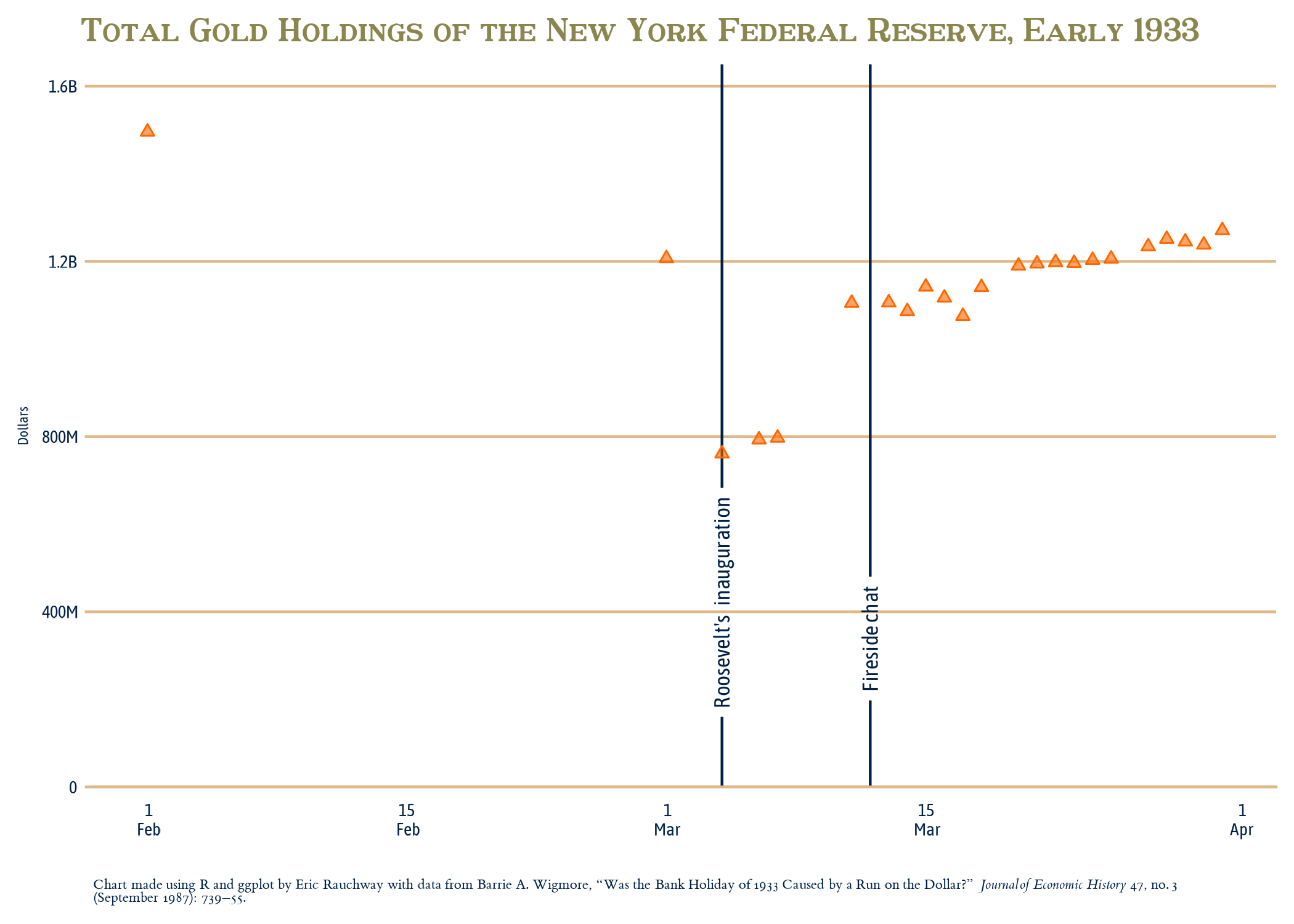

But immediately on taking office, Roosevelt began the process of devaluing, and the panic ended. Here’s Wigmore’s own data of daily gold holdings in the New York Federal Reserve Bank, charted.

Wigmore’s argument is that Roosevelt’s immediate actions might have done something to restore confidence, but not much.

There is no doubt that his inaugural speech, his fireside chat about the banking system, the various measures he rushed through Congress, and his general ability to take command had a very favorable impact on confidence. Measurement of this impact is highly subjective, but intuitively it cannot be a large part of the explanation.

And yet depositors brought much of the gold they had withdrawn back to Federal Reserve banks over the course of March—before Roosevelt’s April 5 order requiring them to do it. Indeed, as you can see from the chart, the steepest rise in gold holdings comes between the inauguration and the fireside chat.

During that time, in his first presidential press conference, on March 8, 1933, Roosevelt allowed as how, according to a definition of the gold standard he pulled from the newspaper, the United States wasn’t on it at the moment, shied away from the term “controlled inflation,” and then almost immediately said,

What you are coming to now really is a managed currency, the adequateness of which will depend on the conditions of the moment. It may expand one week and it may contract another week. That part is all off the record.

A reporter asked if they could print “that part—managed?” Roosevelt replied, “No, I think not.” A little later a reporter pressed him further on what he meant.

Q When you speak of a managed currency, do you speak of a temporary proposition or a permanent system?

THE PRESIDENT: It ought to be part of the permanent system—that is off the record—it ought to be part of the permanent system so we don’t run into this thing again.

Two days later, when he announced the plan for reopening banks, he noted this would include all usual banking functions—

Except, of course, for as to gold. That is a different thing. I am keeping my finger on gold.

These press conferences are now online here as they were not when I was writing The Money Makers, in which I discuss this period.2

In any case, it looks as though Roosevelt was certainly letting the information get out, albeit off the record, that he wanted a permanent system of managed currency and that he wasn’t allowing gold convertibility—and yet, during that time, depositors brought an awful lot of gold back into the Federal Reserve banks. It seems to me that confidence in the new administration’s actions—the first stages of a devaluation—restored some confidence even though they constituted precisely what people were supposed to have feared.

Footnotes

Barrie A. Wigmore, “Was the Bank Holiday of 1933 Caused by a Run on the Dollar?” Journal of Economic History 47, no. 3 (September 1987): 739--755.↩︎

Eric Rauchway, The Money Makers: How Roosevelt and Keynes Ended the Depression, Defeated Fascism, and Secured a Prosperous Peace (New York: Basic Books, 2015).↩︎