Franklin Roosevelt told George VI during the king’s visit to the United States early in June 1939 that the Americans planned to control an area extending five hundred miles east of the U.S. coast, if it could use bases at Bermuda and Trinidad; by the end of the month, the president was meeting with the British ambassador, Ronald Lindsay, to formalize the request for leases at Bermuda, Trinidad, and St. Lucia.1 In retrospect we can identify these plans as an early phase of what became Admiral Stark’s Plan Dog, providing for naval assistance to the Allies in the western Atlantic. Late in July, the Army asked for bases in Trinidad and Natal, Brazil; the Navy confirmed its need of bases, and on August 24, Stark wrote Roosevelt to confirm that leases were available in Trinidad and in Bermuda, where the US Navy would take over some or all of the facilities then operated by Pan American Airways and Imperial Airways. Two days later, the Soviet news agency TASS would issue the terms of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, allocating to the USSR a “special position” in the Baltics and the division of Poland between the two; the Germans and the Soviets began the invasion of Poland shortly afterward.

On September 4, the day after the British declaration of war on Germany, the United States finalized leases to bases in Bermuda, Trinidad, and St. Lucia, paying a rent of $500 a year for the site in Bermuda; on September 6, Stark directed the commander of the Atlantic squadron to maintain a patrol of 300 miles offshore, and to report the movements of foreign men-of-war. Some of the destroyers thus tasked went to Newfoundland as the Grand Banks Patrol, with the acquiescence of the British government, to render assistance in emergencies and to observe and report movements of foreign warships.2

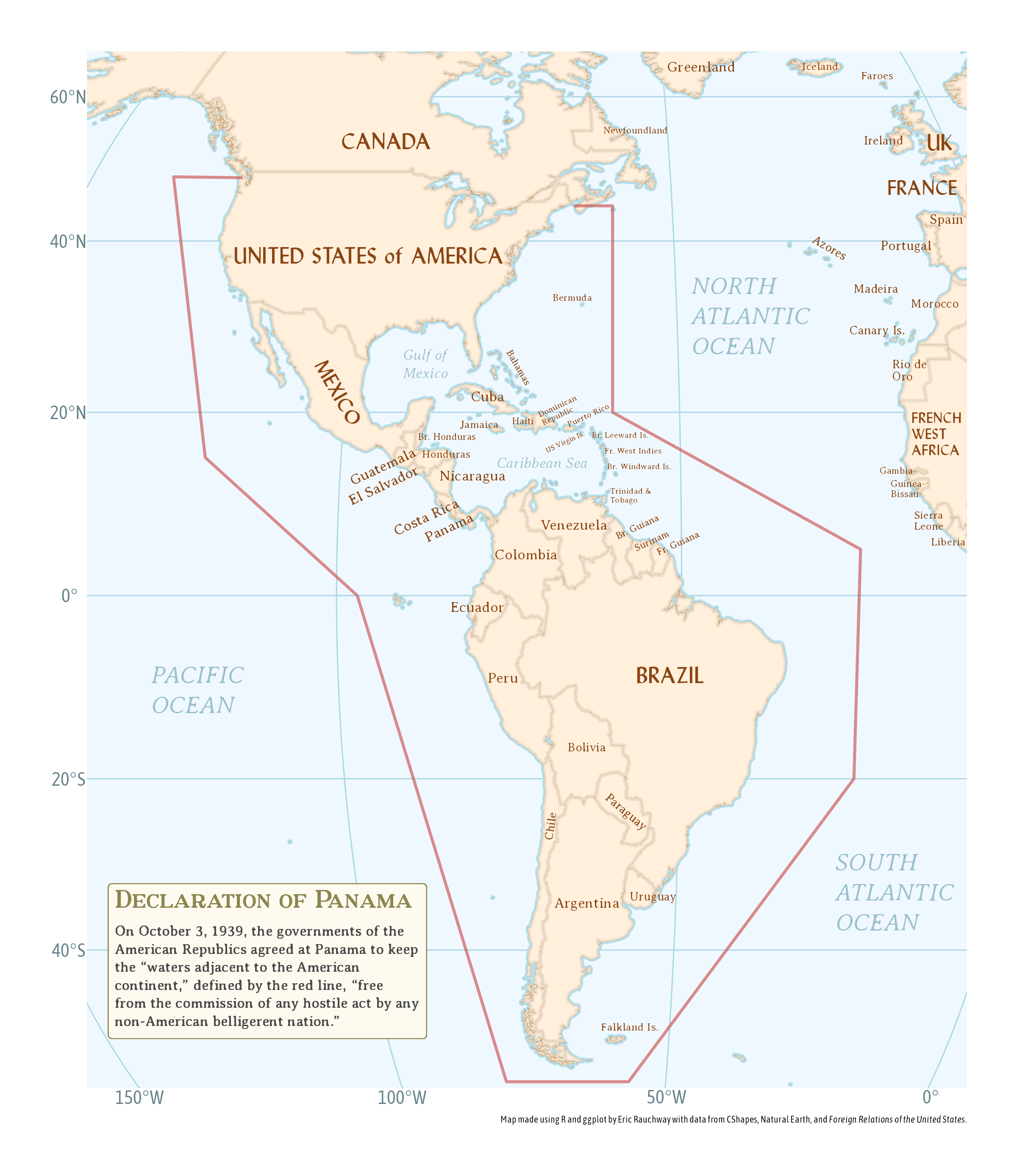

The Division of the American Republics in the U.S. State Department asked the Office of the Geographer to prepare maps with 300-mile radiuses laid out from the outermost limits of the American Republics, and sent that map to the White House, where the president selected the points of a zone defined by those varius circles, and returned it to the geographer with a request to neaten up the map thus defined. The Declaration of Panama, of October 2, 1939, formalized that zone.

Britain allowed unlimited U.S. overflight of the Bahamas after the Panama Declaration. This declaration looked neutral and formally was neutral, though Roosevelt plainly intended it as a form of neutrality that would aid the Allies. As he told Lindsay’s replacement, Lord Lothian, on August 30, 1939, the declaration would allow

all the American republics to combine to patrol half the distance to the coast of Europe and the African coast to prevent entry by belligerent war vessels or acts of war. . . . that would be of great assistance to England and France because it would relieve strain on their navies and would make possible safe transport of food and war materials from Pan-American coasts say, to Halifax, whence they would be conveyed to Europe in Allied bottoms thus lessening the strain on shipping as a whole.3

With the adoption of the Neutrality Act of 1939 in November, this shipping would include arms bound for the Allies.

Footnotes

F.A. Baptiste, “The British Grant of Air and Naval Facilities to the United States in Trinidad, St. Lucia and Bermuda in 1939 (June–December),” Caribbean Studies 16, no. 2 (July 1976): 14–16.↩︎

Robert J. Cressman, The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 2–3.↩︎

Baptiste, “British Grant,” 16.↩︎