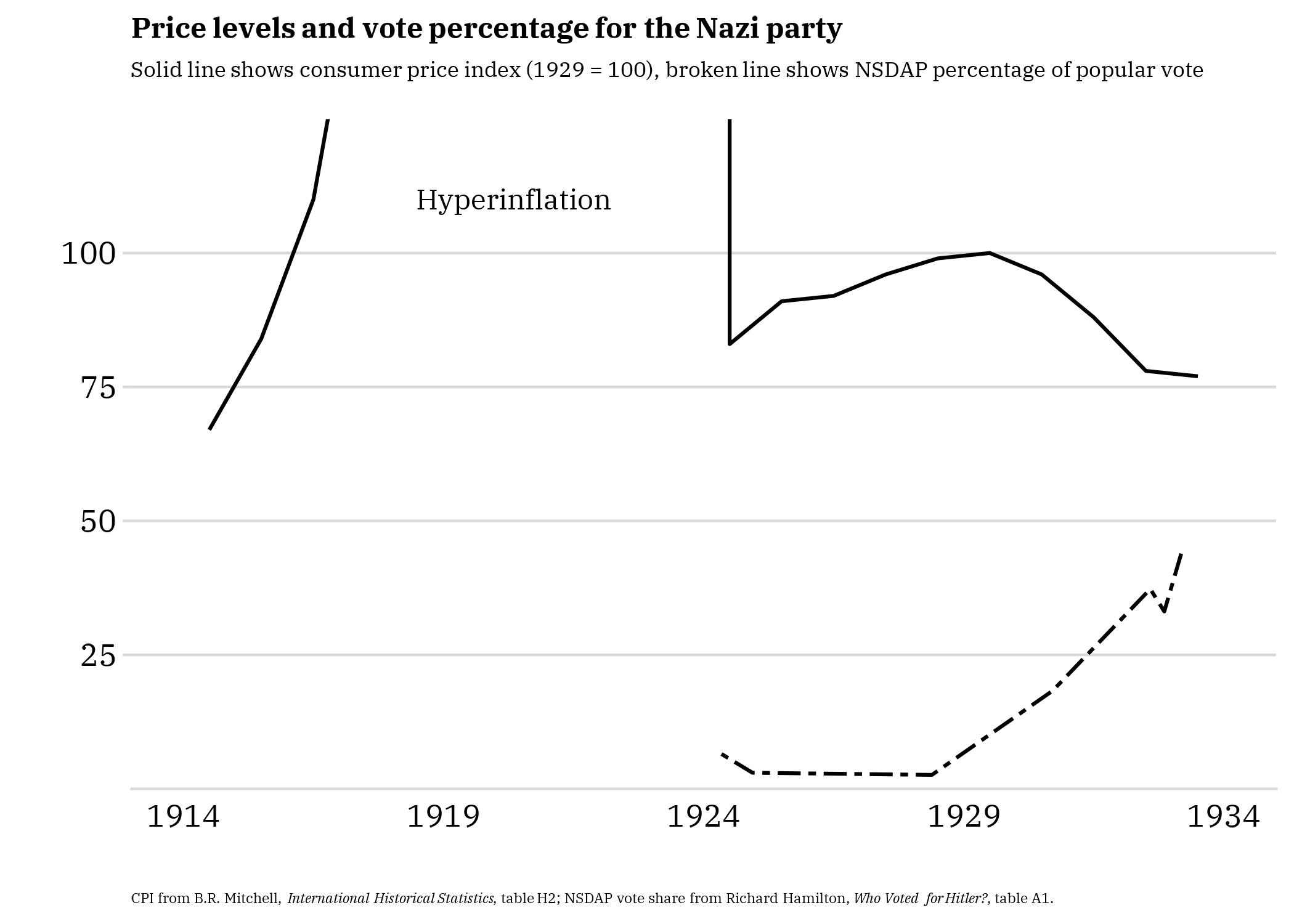

People will commonly blame the Weimar hyperinflation for the rise to power of the Nazi party, disregarding the ten-year lag and the intervening Great Depression, an episode of severe deflation. Recently one historian set forth a “precise mechanism” for how inflation produced antisemitism:

In stable times, we expect each partner in a commercial transaction to believe that the price was fair, and that both sides benefit from the exchange. I buy a meal that satisfies my hunger, and the innkeeper in return has money that can be used to satisfy their needs. When prices move [sic; it should say “rise”], I am upset by having to pay more. The innkeeper is angry because the money I have given no longer buys so many goods. We both think that we have lost out in the transaction, [to this point, the characterization seems fine, if naïve: it’s in the next word that I begin to disagree] and that we have been manipulated by some sinister force. We also feel guilty for taking advantage of others—getting rid of our banknotes as soon as possible. We start to think that we are behaving in a speculative and grasping way. Non-Jewish Germans after the First World War in the middle of the currency disorder thus took up activities that they associated with Jewish actions, hated themselves for their breach of traditional norms, and externalized that powerful emotion by blaming the groups associated with finance and money.1

It seems to me that this explanation fails on two grounds. First, unless you already associate Jews with “speculative and grasping” behavior and are prone to see them as involved in sinister conspiracies to do with money and finance—unless, that is, you are already an antisemite—there is no reason for inflation to lead to extreme antisemitism. The problem isn’t inflation, it’s antisemitism.

Second, if this the mechanism, then shouldn’t it be reversed by deflation? In those transactions, the author’s non-Jewish German should be grateful to have to part with less money than previously; the author’s innkeeper should be pleased to be able to buy more with his money than before; both should be happy that the groups they associate with finance and money have treated them thus . . . yes, well, I grant it’s implausible—because we’re talking about a deeply antisemitic culture. The fault lies not with rising prices, but with antisemitism.

Moreover, of course, it’s not the Weimar hyperinflation that correlates with the increasing power of Nazism. It’s the deflation of the Great Slump, 1928 (in Germany) to 1933.

Which is why, of course, the economist George Warren observed at the time, “It seems to be a choice between a rise in prices or a rise in dictators.”2