Below are my comments, as prepared, from the Washington History Seminar session of October 16, 2023, if you’d like to read them. If you’d like to see the whole session as it actrually transpired, video is at this link. Thanks to Eric Arnesen, Christian Ostermann, and Rachel Wheatley for organizing the session on behalf of the American Historical Association and the Woodrow Wilson Center’s History and Public Policy Program.

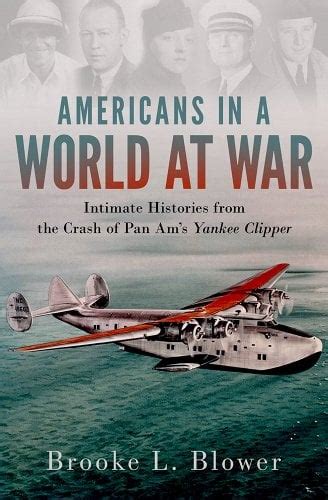

I want first of all to congratulate Brooke on this book, which is as readable a work of history, and as fascinating a narrative, as I have come across in a long time.1 I can assure you it will fill a spot on a number of my holiday gift lists this year, and I imagine it will do the same for many people listening; it is a handsome book and will, I suspect, be a welcome gift for the readers you know, so make a note wherever you make your notes about what to get people for the holidays.

It’s a beautifully conceived book: that is, it’s one thing to think of writing a book around the uncertain time in 1943 when it was not yet clear that the Allies would win the war, but it’s a stroke of genuine inspiration to ground that book in this particular, dramatic event—the crash of Pan Am’s Yankee Clipper—and to use the lives of the people on board to develop all the ways that uncertainty and that war manifested themselves in individual lives.

Perhaps still more extraordinary, it’s a good idea that is exceptionally well executed. You’ve pursued, methodically and carefully, a wide range of sources, familiarizing yourself with the histories of politics, business, law, theater, aviation, shipping, and much more. In so doing, you’ve demonstrated an active and empathetic historical imagination, an ability to envision and then to encompass the strange old world of a vanished past.

So the book is not only beautifully conceived, but carefully constructed, which is a rare combination indeed.

For the purposes of sparking further discussion, I’d like to highlight two points.

First, the book really does show you, as the title says it will, a variety of Americans experiencing the world at war—not just from 1939 or 1931, or whenever you date the beginning of the Second World War, but really from 1914 onward, as your section titles indicate. And so—one of the things I really like about his book is that it’s narrative, rather than argumentative; you show, rather than tell—but for the purposes of our discussion here it might be appropriate for you to show your hand a bit more—so it seems to me you’re taking the position, taken by Winston Churchill and many others before you, that this is essentially the twentieth century’s Thirty Years War, a continuous event from 1914 through to 1945, and properly embraced as such.2

Now, as I say that’s not an uncommon position to take, but it’s one that might have interpretive implications that, in a book like this, run under the surface, but I wonder if you could draw them out. How does it change your understanding of the Second World War to say that it’s really of a piece with the First?

So that’s my first question.

Okay, now for a second point. I’ve been very complimentary to this point, so I hope you won’t mind the least critical remark possible: I don’t think you needed to be even a tiny bit defensive, as I did think you were in the closing “note on method,” about writing a book about the Second World War. I think this is a subject that falls squarely into the category of “things that are endlessly popular because they are, in fact, endlessly interesting.” You would have had to apologize, perhaps, if you’d written a book that simply trundled over known territory and known evidence—which of course many people do. Which is why, for example, when Max Hastings wrote his one-volume survey in 2011 he set himself the challenge of using “relatively obscure anecdotage at the expense of justly celebrated personal recollections,” as he put it.3

Now, the structure of your book leads you to all kinds of areas and byways which do this naturally, that is, you follow the people’s stories where they go—so we hear about the fascinatingly gray area of trade with neutral, but Axis-aligned, Spain, which we don’t often get to; we hear about some of the actual mechanics of Lend-Lease, which was a wonderful, world-wide system, a genuine logistical achievement, which is usually just sort of waved at. When you talk about some of Frank’s broadcasts, you talk about the challenge he faced in trying to “make real” the complex web of connections in the Pacific world, this legacy of empire transformed by the exigencies of war. You get a lot of wonderful anecdotage of your own because of it. I was especially taken with the sad side effect of the Nazi-Soviet Pact on Tamara’s production—that is, “Dancing Stalin would have to be cut.” What a wonderful line.

I’m curious, though: in writing a book about people to whom, for the most part, the war is happening—they are Americans In a World At War, not “waging a world war,” or something like that—which I think correctly describes the felt experience of most Americans, that this war happened to them. And that effect is I think amplified by your choice of date; after all, this crash happens, and the book ends, just at the point when the United States really began to take much more of a leading role in the war.

So that’s my second question: what do you think it does for our understanding of the Second World War, to narrate it more as an event that happened to Americans, rather than one in which they were in the drivers’ seat?

Footnotes

Brooke L. Blower, Mary L. Dudziak, and Eric Rauchway, “Americans in a World at War: Intimate Histories from the Crash of Pan Am’s Yankee Clipper” (Washington History Seminar of the American Historical Association, October 16, 2023).↩︎

Winston S. Churchill, The Gathering Storm (London: The Reprint Society, 1950), ix.↩︎

Max Hastings, Inferno: The World at War, 1939–1945 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), xix.↩︎